Print Article

- Introduction

- De-escalation zone

- Russian Ministry Statement of Denial

- Protected status of medical personnel

- About this report

- methodology

- workflow

- A. Identification

- B. Collection and secure preservation

- C. Processing, verification, and analysis

- D) Review

- E) Publication

- Errors, Corrections, and Feedback

- Incidents

Table Of Contents

Introduction

In the period between 03 January 2018 and 05 February 2018, four hospitals in Idlib governorate well within the De-Escalation Zones established by Russia, Turkey and Iran during the Astana talks were attacked by airstrikes that visual documentation, witness statements, and flight observation data attributes to Syrian or Russian forces. Three of these hospitals were attacked within the span of a week.

This report was written as a followup to a July 2017 report titled titled Medical Facilities Under Fire: Systemic Attacks during April 2017 on Idlib Hospitals., in which detailed reports of eight hospitals or medical facilities targeted within one month in one province (Idlib) were published jointly by the Syrian Archive, in partnership with Syrians for Truth and Justice, Justice for Life, Bellingcat and a flight observation organisation.

Findings in this previous report suggest that in April 2017, Syrian and Russian armed forces were responsible for the eight attacks on Syrian hospitals and healthcare centres - facilities in Idlib serving a combined 1.3 million people (a beneficiary group larger than the population of Brussels), as reported in witness statements as well as by the managers of those medical facilities. Subsequently, the United Nations’ Commission of Inquiry presented findings of a fact-finding mission confirmed the systemic targeting of medical facilities by the Syrian government in April 2017, as well as the illegal use of chemical weapons.

De-escalation zone

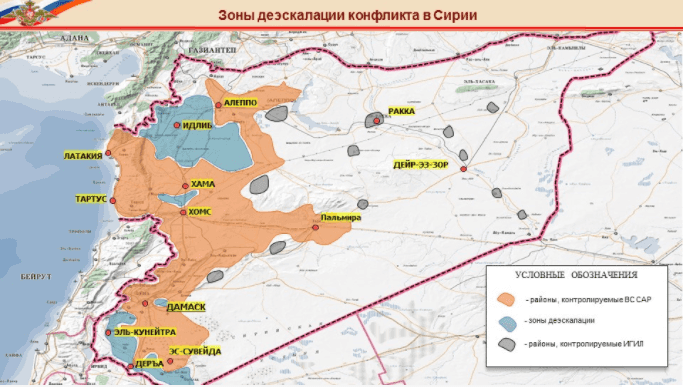

On 4 May 2017, the sponsoring states of Astana Talks (Russia, Turkey, and Iran) signed a memorandum of understanding for the establishment of de-escalation zones in Syria for at least six months, which was extended at Astana 7 on 31 October 2017. The Russian Ministry of Defense published a map showing the locations included in this memorandum as shown below (de-escalation zones in blue, ISIS in grey, Syrian army in orange). See below:

These areas included Idlib province, some parts of northern Homs province, as well as some parts of adjacent provinces (Latakia, Hama, and Aleppo), Eastern Ghouta in Damascus countryside and some parts of southern Syria.

Just four days after the Astana International meeting establishing Syria’s De-Escalation Zones in many parts of the country, three Idlib medical facilities serving a combined more than 100.000 people yearly were allegedly attacked in airstrikes attributed to Syrian or Russian forces on a single day.

Now, six months later, little has changed. Hospitals remain at the frontlines of the Syrian conflict, and attacks against medical facilities are regular.

Russian Ministry Statement of Denial

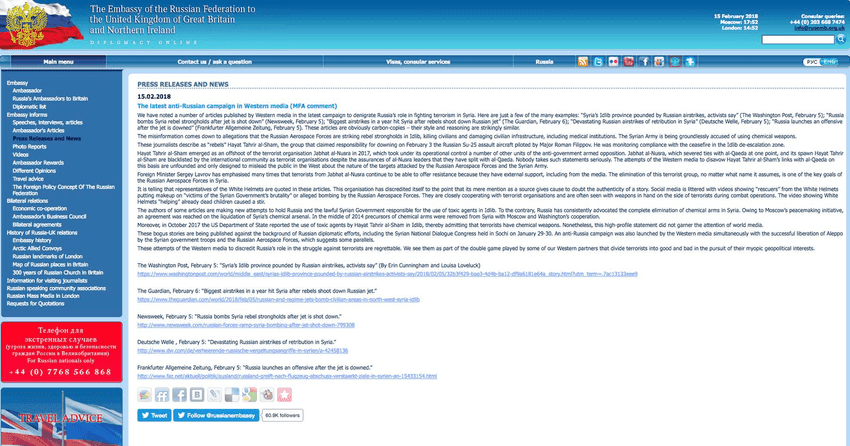

The first week of February 2018 has shown a flurry of media attention focused on potential Russian involvement in the bombing of civilians in Syria. In response, the Russian Embassy to the United Kingdom published a press release on 15 Feb. 2018 claiming a misinformation campaign by “Western media.” The press release claims “the misinformation comes down to allegations that the Russian Aerospace Forces are striking rebel strongholds in Idlib, killing civilians and damaging civilian infrastructure, including medical institutions.” See below:

This statement, implies (though does not outrightly deny) that Russian airforces are not responsible for the bombing of civilian infrastructure, including hospitals and medical facilities. Later, the same press release states that “on February 3 the Russian Su-25 assault aircraft piloted by Major Roman Filippov…was monitoring compliance with the ceasefire in the Idlib de-escalation zone” at the time his plane was shot down.

That four Idlib hospitals were targeted by airstrikes within a four week period indicates that regardless of whether or not Russian aircraft are targeting medical facilities and other protected persons and objects (deliberately or not), Russia, Turkey and Iran have failed in their compliance enforcement of the de-escalation zones. Through analysis of flight observation data for 4 Feb. 2018 bombing of Maarat al-Numaan National Hospital, for example, several flights were tracked as having taken off from Hmeimim airbase (controlled by Russian forces), flown north, turned around and bombed the National Hospital at 20:40.

In a previous statement by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov regarding the 2016 attack on a humanitarian aid convoy near Aleppo, the Foreign Minister stated: “The Syrian aircraft could not have operated [there], because the attack against the convoy was conducted in the night time and the Syrian Air Force does not perform flights in this time, it has no such capabilities.”

As the Maarat al-Numaan National Hospital was attacked at night, Lavrov’s statement can be interpreted as: 1) inaccurate, as the Syrian Airforce does in fact have the capacity to fly at night, potentially involving them in the 2016 attack on a humanitarian aid convoy; 2) the Syrian Air Force has vastly improved its capabilities since 2016, allowing flights to operate at night and operates out of a Russian airbase, in addition to airbases controlled wholly by the Syrian airforce; 3) Russian aircraft were involved in the attack of Idlib medical facilities; or 4) A third-party operating Russian aircraft from Russian airbases was involved in the attack of Idlib medical facilities, and Russian forces are failing to enforce compliance within their own airbases.

Protected status of medical personnel

Under International Humanitarian Law, medical personnel enjoy a protected status. As part of their protected status, they cannot be targeted by any party to the armed conflict. The law defines medical personnel as, “Personnel assigned, by a party to the conflict, exclusively to the search for, collection, transportation, diagnosis or treatment, including first-aid treatment, of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, and the prevention of disease, to the administration of medical units or to the operation or administration of medical transports.” Moreover, persons performing medical duties who do not fall within this legal definition but are attacked when providing similar medical services enjoy the same protection under International Humanitarian Law.

The principle of proportionality also prohibits parties to an armed conflict from launching attacks that might incidentally harm medical personnel, creating excessive harm in relation to any concrete military advantages gained. Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions further requires that the wounded and the sick be collected and cared for during armed conflict.

About this report

The Syrian Archive and its partners (Syrians for Truth and Justice, and Bellingcat) analysed and verified this pattern of attacks by cross referencing a combination of open-source visual content, flight observation data, and witness statements. Findings regarding these attacks were characterised by repeated bombardments, lack of warnings, and an absence of active military hostilities in the vicinity of the attack. Through collecting, verifying and reporting investigative findings from these incidents, the authors hope to preserve critical information that may be used for advocacy purposes or as evidence in future proceedings seeking legal accountability.

This report includes damage identification, cross referencing and contextualising visual content (50 verified videos) with witness statements (10 people) and with flight observation data (1696 observations) provided by a spotter organisation of aircraft in the immediate vicinity of hospitals at the time of attacks. Geolocation of visual content was done in collaboration with the Bellingcat Investigation Team.

By examining a variety of sources of information for each attack, the Syrian Archive was able to corroborate and strengthen the findings from their visual content dataset. Visual content gathered and verified by the Syrian Archive is extensively analysed - including in-depth geolocation and, when relevant, munition identification.

To cross-reference findings from visual content, flight observation data was provided to the Syrian Archive by an organisation employing a well-developed network of spotters. Following an analysis of the visual content and flight observation data, the Syrian Archive identified excerpts of statements from witnesses and victims collected by Syrians for Truth and Justice combined them with findings from their earlier analysis to provide corroborating witness statements for each attack.

Detailed overviews of each incident are provided in the following pages. An overview of the visual content is provided first, followed by an overview of the corroborating flight observation data and witness statements. All times provided are in Damascus local time, and in 24-hour format. Prior to publication, consent was acquired with those interviewed (e.g. medical workers, facility managers, and Civil Defense volunteers) regarding the public sharing of information regarding attacks.

methodology

This report took an interdisciplinary approach towards investigating attacks on medical facilities in Idlib during January and February 2018. In the report, the authors have included a variety of sources for analysis and investigation, which each have their own respective methodologies. Specific methodologies are provided in the following pages:

Witness Statements

Following the hospital attacks in Idlib province during the month of January and February 2018, Syrians for Truth and Justice established a field research team which was tasked with entering the city and inspecting the impact sites. These organisations were additionally tasked with collecting material evidence as well as accounts of the survivors, such as those injured and their families, as well as accounts of eyewitnesses (e.g. medical staff; managers of the hospitals; civil defense team members).

Interviews were conducted in person in Idlib by staff members of their respective organisations and recorded on audio devices and then later transcribed. Staff members conducted a total of 10 semi-structured interviews using a standardised questionnaire. Questions asked to respondents focused on the following themes:

Details surrounding the attack (e.g. date, time, location)

The number of patients each medical facility provided care to on a monthly basis

The types of departments or procedures medical facilities conducted

The geographic areas served by medical facilities

Whether this medical facility had been previously subject to attack

Information regarding casualties and those injured as a result of the attack

Flight Observation Data

To cross-reference with findings from visual content, flight observation data information was provided to the Syrian Archive by an organisation employing a well-developed network of spotters (flight observers) of aircrafts departing from military air fields primarily located in northwestern and central Syria.

Flight data and the visual content were analysed to identify whether flights were observed in the vicinity of locations attacked for locations in which aerial bombings were alleged.

Visual Content

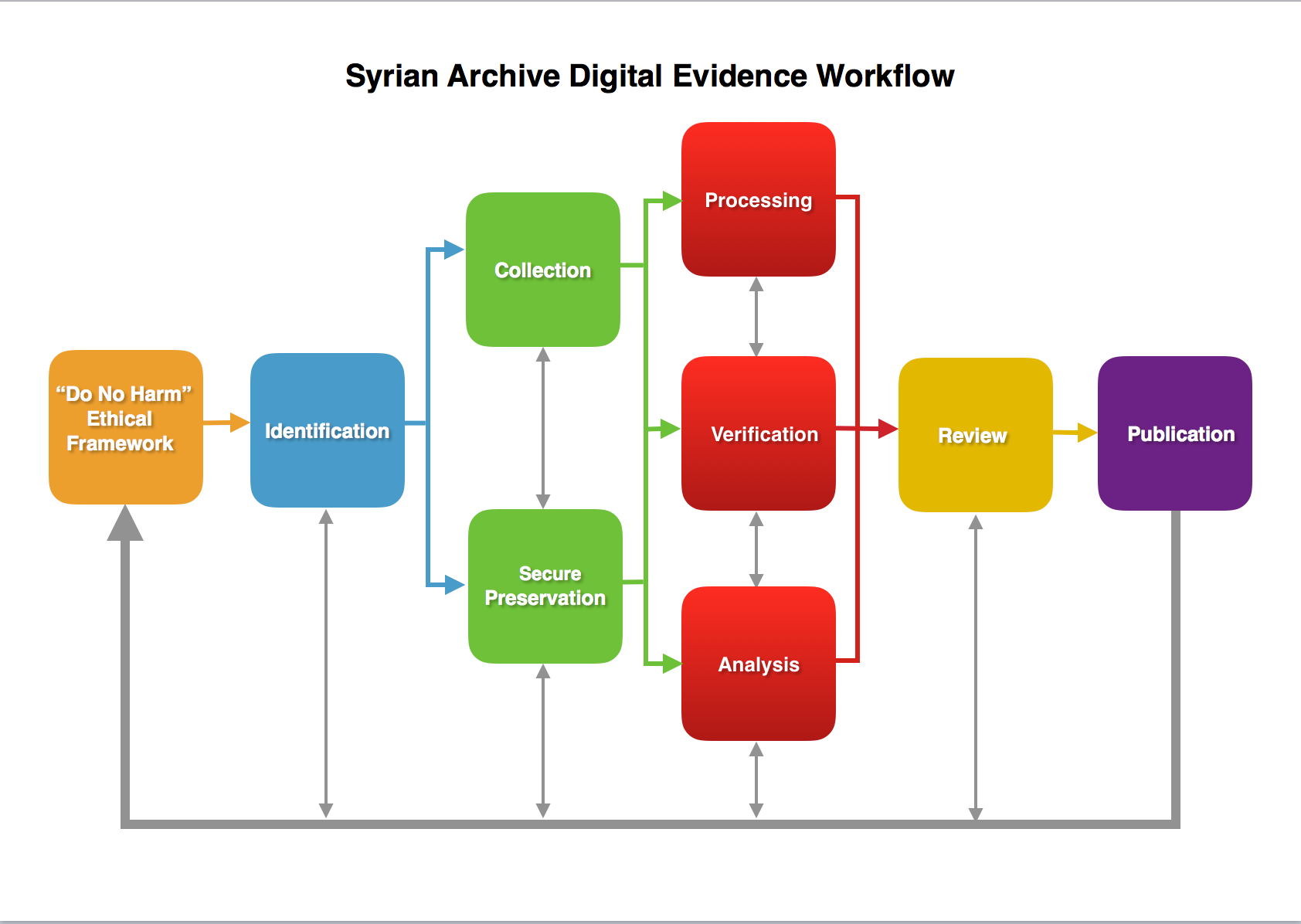

The Syrian Archive employed its Digital Evidence Workflow, based off of the Electronic Discovery Reference Model developed by Duke University School of Law. This workflow consists of five components: A) Identification; B) Collection and secure preservation; C) Processing, verification and analysis; D) Review; and E) Publication. A “Do No Harm” ethical framework has been applied to all steps in the digital evidence workflow. Detailed methodologies of these components are analysed in the following subsections.

A. Identification

The Syrian Archive’s identification process has three steps: 1) Establish a database of credible sources for digital content; 2) Establish a database of credible sources for verification; 3) Establish a standardised metadata schema. These three processes are outlined in detail below:

- Establish database of credible sources for content

Before any collection, archival, or verification of digital materials was possible, the Syrian Archive first established a database of credible sources for visual content. The Syrian Archive project worked to identify over 3000 credible sources, a list consisting of individual journalists and field reporters, larger media houses (e.g. local and international news agencies), human rights organisations (e.g. Syria Institute for Justice), Syrian Civil Defense (White Helmets), and local field clinics and hospitals, and others. Many of the sources used by the Syrian Archive began publishing or providing visual content in late 2011-early 2012 and have also published work in other credible media outlets.

Credibility was determined by analysing whether the source is familiar to the Syrian Archive or to its existing professional network of Syrian journalists, media activists, human rights groups and humanitarian workers; whether the source’s content and reportage been reliable in the past. This is determined by evaluating how long the source has been reporting and how active they are. To determine where the source is based, social media channels are evaluated to determine whether videos uploaded are consistent and mostly from a specific location where the source is based, or if locations differ significantly. Channels are analysed to determine whether the video account uses a logo and whether this logo is consistently used across videos. Channels are additionally analysed for original content to determine whether the uploader aggregates videos from other news organisations and YouTube accounts or whether they upload mostly user-generated content.

- Establish database of credible sources for verification

Secondly, the Syrian Archive project worked to establish a database of credible sources for verification. These sources provide additional information used for verification of content originating on social media platforms or sent from sources directly. Those verifying content are made up of citizen journalists, human rights defenders and humanitarian workers based in Syria and abroad. To preserve data integrity, sources used for content did not comprise part of the database for verification.

- Establish standardised metadata scheme

Third, the Syrian Archive recognised the need for a standardised metadata scheme for organising content, but also that any metadata scheme used would be a highly political choice. Given that there are no universally accepted legally admissible metadata standards as of the date of this publication, efforts were made to develop a framework in consultation with a variety of international investigative bodies. Among these include consultations with members of the International Criminal Court, with members of the United Nations Office for High Commissioner of Human Rights, with members of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on international crimes committed in Syria (IIIM), with archival institutes like the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, with international human rights organisations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Witness, and with research institutes like the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley School of Law.

Establishing a standardised metadata schema is necessary in order to assist users in identifying and understanding when, where, and what happened in a specific incident. A review of practices by other war archival institutes, such as those of NIOD, found that additional information is helpful for contextualising raw visual content (e.g. location of video recording; date of video recording and upload; and the origin of the video). Metadata collected by the Syrian Archive project includes description of the visual object as given (e.g. YouTube title); the source of the visual content; the original link where footage was first published; specific landmarks able to be identified; weather (which may be useful for geolocation or time identification); specific languages or regional dialects spoken; clothes or uniforms able to be identified; weapons or munitions used; device used to record the footage; and media content type. The metadata is populated automatically and manually depending on how it was collected from e.g open source or closed source. A detailed description and full list of metadata field types are provided on the Syrian Archive website.

In categorising violations, the Syrian Archive has decided to use the violations categories used by the Office of United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). This was done because OHCHR is one of the groups in the unique position of being able to investigate incidents of human rights violations and war crimes. These categories consist of many often overlapping categories. Categories identified by the UN OHCHR Inquiry on Syria and used by the Syrian Archive project include:

Violations: treatment of civilians & hors de combat fighters

- Massacres and other unlawful killing;

- Arbitrary arrest and unlawful detention;

- Hostage-taking;

- Enforced disappearance;

- Torture and ill-treatment of detainees;

- Sexual and gender-based violence;

- Violations of children’s rights;

Violations: conduct of hostilities

- Unlawful attacks;

- Violations against specifically protected persons and objects;

- Use of illegal weapons;

- Sieges and violations of economic, social and cultural rights;

- Arbitrary and forcible displacement.

Should potential investigations by international bodies not be pursued by the UN OHCHR and rather by another investigative body, it is anticipated that the Syrian Archive will modify violations categories to meet the needs of those investigating.

B. Collection and secure preservation

The collection and secure preservation of the digital evidence workflow ensures that the original content is not lost due to removal on corporate platforms. This is done by collecting and securely storing digital content on external backend servers before it goes through basic verification. It is then backed up securely on servers throughout the world. Videos are hashed with (SHA-256) and (Md5) consistent with current best practices and timestamped to ensure they are not tampered with after being collected from social media platforms (open source) or taken directly from sources (closed source). Simultaneously it is hashed and timestamped by an independent and impartial third party for reference and integrity purposes. Once verified, content is centrally published on the Syrian Archive website in an open-source format. The Syrian Archive uses the SugarCube software for this process, a free and open source software developed for use in human rights investigations using online-based user generated content research.

C. Processing, verification, and analysis

After content has been collected and stored securely, the next stage of the digital evidence workflow refers to the processing, verification, and analysis of digital materials. Detailed descriptions of these three components of the digital evidence workflow are outlined below:

- Processing

Metadata from visual content collected from social media platforms is parsed and aggregated automatically using a predefined and standardised metadata scheme, as described above. Metadata from visual content sent to the Syrian Archive directory is created manually using the standardised metadata scheme.

This prepares the visual content for initial verification. As much additional metadata and chain of custody information as possible is recorded. This is done to assist users in identifying and understanding when, where, and what happened in a specific incident.

- Verification

Verification is comprises of three components: 1) Verify the source of the video uploader; 2) Verify the location where the video was filmed; 3) Verify the dates in which the video was filmed and uploaded. Detailed descriptions of these three processes are outlined below:

- Verify the source of the video uploader

Establish that the source of the video on the Syrian Archive’s verified list of credible sources. If the source is not an existing trusted source, determine the new source’s credibility by going through the procedure highlighted above.

In some cases, near-duplicate content may be published. For example, if one video is 30 seconds and a second video is 10 minutes but includes all or portions of the first video, both videos would be published as long as it is possible to verify both videos. Similarly videos from news organisations or media houses featuring all or parts of content from other videos are also preserved, as long verification is possible. The Syrian Archive also preserves duplications if they are from different sources and the original uploader is unable to be determined (for example if two identical videos are uploaded simultaneously).

The video uploader source may not necessarily be the same as the source who originally filmed content. In most of the video footage verified by the Syrian Archive, only the video uploader and not the video filmer is known. Advanced verification in the analysis phase includes the source of filming, a process done in cases deemed priority.

- Verify the location where the video was filmed

Each video goes through basic geolocation to verify that it has been captured in Syria. More in-depth geolocation is conducted for priority visual content in order to verify that it has been captured in a specific location. This has been done by comparing reference points (e.g. buildings, mountains ranges, trees, minarets) with Google Earth satellite imagery, Microsoft Bing, and Digital Globe, as well as OpenStreetMap imagery and geolocated photographs from Google Maps. In addition to this, the Syrian Archive has referenced the Arabic spoken in videos against known regional accents and dialects within Syria to further verify location of videos. When possible, the Syrian Archive has contacted the source directly in order to confirm the location, and cross-reference video content by consulting existing networks of journalists operating inside and outside Syria to confirm the locations of specific incidents.

- Verify the dates in which the video was filmed and uploaded

The Syrian Archive verifies the date of capturing the video by cross referencing the publishing date of visual content collected from social media platforms (e.g YouTube, Twitter, Facebook and Telegram) with dates from reports concerning the same incident. Visual content collected directly from sources is also cross referenced with reports concerning the same incident featured in the video.

- News reports from international and local media outlets, including Reuters, Smart News Agency, Aleppo Media Center, Qasioun News Agency, LCC;

- Human rights reports published by international and local organisations, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Syrian Human Rights Network, Violations Documentation Center in Syria, Syrian American Medical Society, and Physicians for Human Rights;

- Reports shared by the Syrian Archive’s network of citizen reporters on Twitter, Facebook and Telegram about the incidents.

Additional tools are used to check the date of the visual content such as Google reverse imagery and Sun Calc.

- Analysis

In some cases, the Syrian Archive is able to conduct in-depth open source investigations. Time and capacity limitations means not all incidents are able to be analysed in-depth, however by developing a replicable workflow it is hoped that others can assist in these efforts of investigate other incidents using similar methods. A detailed overview of in-depth incident analysis is provided in the investigations section of the Syrian Archive website.

D) Review

Once digital materials have been processed, verified, and analysed, it is then reviewed for accuracy. In the event of a discrepancy, content is fed back into the digital evidence workflow for further verification. If content is deemed accurate it moves to the publishing stage of the digital evidence workflow.

E) Publication

Once the visual content is verified and reviewed, it’s then published on the Syrian Archive database where they are made publicly available in a free and open source format. Regular reports on verified visual content ensure that the feedback loop between the Syrian Archive and sources who filmed the videos is closed. This allows the Syrian Archive to add value to the visual content being preserved, verified and analysed immediately for advocacy purposes and later on for accountability and justice purposes.

Errors, Corrections, and Feedback

The authors of this report have strived for accuracy and transparency of process in reporting and presentation, while balancing the need to protect the safety of those providing documentation in some instances. With these interests in mind, detailed methodologies for some information deemed sensitive have not been published.

With that said, while all efforts have been made to present our best understanding of alleged incidents, it is recognised that the publicly available information for specific events can at times be limited.

If readers have new information about particular events; find an error in our work - or have concerns about the way we are reporting our data - please do engage with us. You can reach us at info@syrianarchive.org.